Kotsopoulos S, Ph.D. Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2005

II. Shape Computation Theory

1. Introduction

2. Computational Theory

3. Computational Design Theory

4. Shape Computation

4.1. SHAPE CALCULUS A B C

At a perceptual level Stiny (1996) emphasized that the attribution of structure is not intrinsic in shapes. Names,

values and meanings used by convention as a means of identification are the result of retrospective analysis.

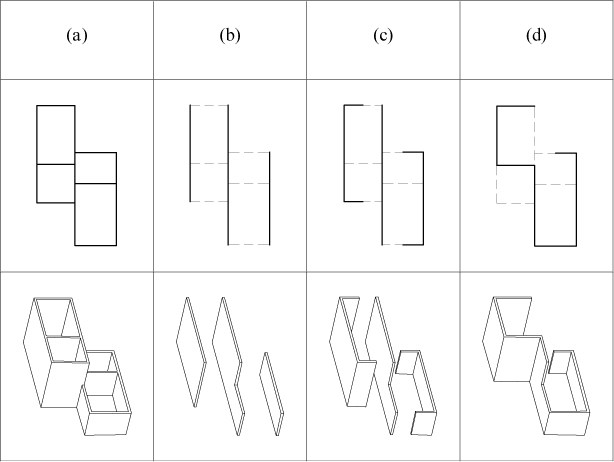

The possible interplay between form and meaning opens a vast field of creative exploration. The next simple

diagram presents some of the alternative structures that one may retrieve from the initial arrangement of the

example: I-shaped structure, C-shaped, or W-shaped structure.milarly, the next arrangement made out of solids

representing walls.

a W-shaped structure in (d)

sets whose members are closed under a set of operations. In the construction of shape algebras the spatial

elements are classified in the Euclidean fashion in four sets containing points, lines, planes and solids

respectively. Each algebra Uij contains elements of dimension i = 0, 1, 2 or 3, that are manipulated in dimension

j = 1, 2, or 3, so that j >= i. Each set Uij is closed under the operations of sum and product.

Each shape-algebra does three things: First, it allows the execution of operations with shapes, second it allows

shape-manipulation with the Euclidean transformations, and third it provides a formal ground for the study of the

relationship between shape and structure. Due to Stiny 1991 the shape-algebras are classified in the next table,

U00 U01 U02 U03

U11 U12 U13

U22 U23

U33

For i = 0, the algebras contain points. For example the algebra U00 is formed by a single point. For i = 1, 2 and 3

the algebras contain lines, planes and solids. Shapes made out of lines belong to the U1j row of algebras. Each

shape is defined as a finite set of lines of finite and possibly zero length, maximal with respect to one another,

manipulated on a line (U11), a plane (U12), or, in space (U13). Shapes made out of planes can be found in the

U2 j row of algebras. Each shape is defined as a finite set of planes of finite and possibly zero area, maximal with

respect to one another, manipulated on a plane (U22), or in space (U23). Shapes made out of solids belong to

U33 algebra: Each shape is defined as a finite set of solids of finite and possibly zero volume, maximal with

respect to one another, manipulated in space.

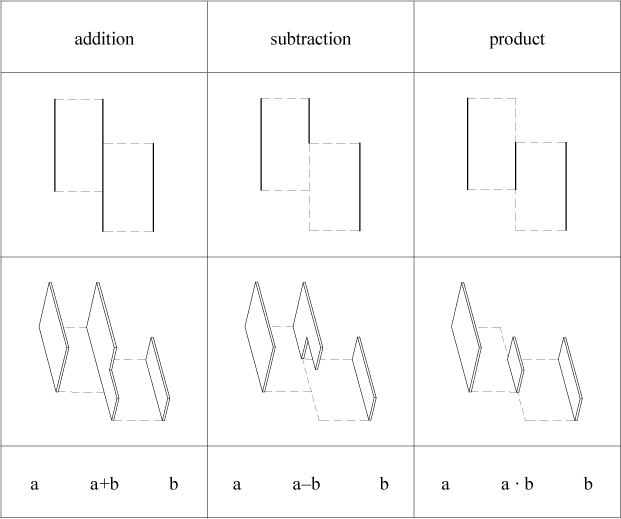

The following example with lines and solids shows how non-atomic elements interact in space. The elements a

and b can be added to produce an element a + b. Or, the element b can be subtracted from a to produce the

difference a – b. The product a • b denotes the common part of a, b.

In all examples, shape a appears on the left, and shape b on the right. The produced shapes

a + b, a - b, a • b appear between a and b.